Examining Economics Through the Lens of Colonialism

Overview

- This year's Nobel Prize vividly highlights the essential role of institutions in shaping economic development.

- Critics strongly argue that the laureates' framework fails to acknowledge the lasting damage caused by colonialism.

- Real-world examples compellingly demonstrate that nations can experience substantial growth even without inclusive institutions.

The Nobel Prize Announcement

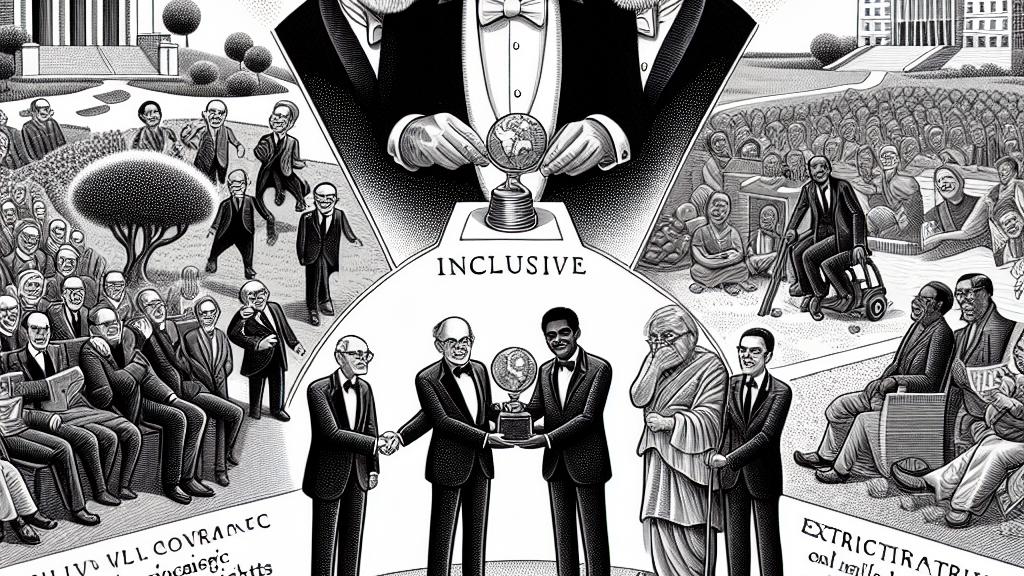

In a momentous announcement in October 2024, the Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded to Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson for their pioneering research on the critical role institutions play in economic outcomes. Their influential studies categorize institutions into two types: 'inclusive' institutions, which champion property rights and democratic governance, and 'extractive' institutions, which limit opportunities and concentrate wealth among a select few. What’s particularly striking is how these findings have sparked spirited debates about the enduring legacies of colonialism that continue to shape economic disparities globally. Consider how nations like Canada, which developed inclusive institutions, have thrived compared to many African nations saddled with extractive structures; this stark contrast highlights the profound effects of institutional choices made during colonial times.

Critiques of the Institutions Framework

Despite the accolades, the laureates’ theories have drawn noteworthy criticism from scholars who question their categorical assertions. Esteemed economists, including Mushtaq Khan and Yuen Yuen Ang, emphasize that many countries—especially those with colonial histories—have indeed experienced remarkable economic growth without establishing inclusive governance first. Look at Singapore and South Korea as prime examples; both nations illustrate that successful economies can thrive even amidst corruption and governance issues. This perspective challenges the idea that inclusive institutions are a prerequisite for development, suggesting instead that other factors, such as strategic policy-making and social capital, play significant roles in driving economic success.

Colonialism's Shadow on Economic Theory

Moreover, a glaring oversight in the laureates' analysis is their limited focus on the brutal impacts of colonialism, which casts a long shadow over contemporary economic realities. They compare outcomes between settler and non-settler colonies but often neglect to examine the harsh histories of violence and subjugation that accompanied these institutional formations. For instance, even in settler colonies that managed to develop successful institutions, initial acts of colonial aggression and exploitation have had lasting effects on indigenous populations. Recognizing these historical dimensions is crucial, as it enriches our understanding of why certain nations emerge as economic powerhouses while others struggle—thus inviting a deeper and more nuanced discussion about the complexities of institutional development and its implications for economic growth across the globe.

Loading...