Understanding the Differences in Car Dependency Between Urban and Rural Living

Overview

- In rural areas, the necessity of owning a car often stems from limited public transportation options.

- Urban residents frequently express their frustration about the perceived burden of car ownership.

- Cultural beliefs surrounding vehicle necessity highlight the stark differences between urban and rural lifestyles.

The Essential Role of Cars in Rural Life

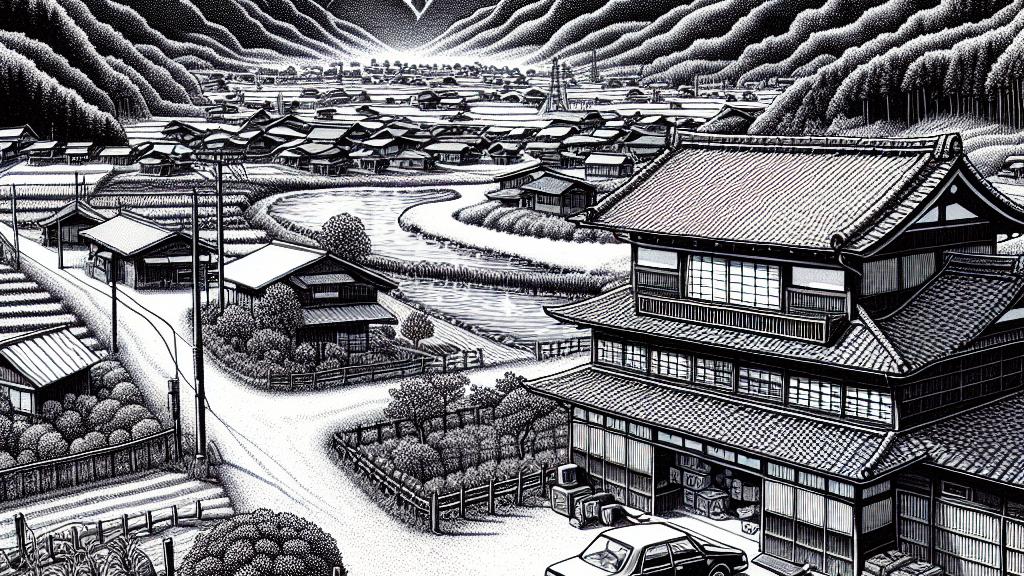

In the vast and often beautiful rural landscapes of Japan, owning a car is not simply a choice; it is a fundamental necessity. Imagine waking up in a tranquil village, where the nearest grocery store is a 30-minute drive away. For local residents, a car becomes as essential as shoes—necessary for daily activities. When urban dwellers say, 'I don’t want to buy a car just to live in the countryside,' rural individuals might shake their heads in disbelief. It's akin to saying, 'I refuse to wear shoes.' In rural areas, vehicles symbolize freedom and ease, allowing people to traverse sprawling distances with minimal hassle. Whether it’s taking the family out for a picnic by a serene river or visiting a neighboring town, a car unlocks countless opportunities for adventure and socialization, reinforcing the deep connection between mobility and rural identity.

Economic Realities of Vehicle Ownership

Economic considerations play a significant role in shaping views about car ownership. While the costs of maintaining a vehicle—including fuel, insurance, and repairs—can certainly add up, rural residents often find these expenses manageable when compared to urban living. Consider this: a city dweller may pay an eye-watering $2,000 monthly rent for a small apartment, while a rural homeowner might enjoy a cozy, spacious property for roughly half that amount. Many residents proudly share stories of finding dependable, second-hand vehicles that serve their needs without breaking the bank. For example, it’s common to hear about someone purchasing a reliable used truck for weekend projects. This makes it clear that owning a car doesn’t just help them get from point A to point B; it also represents economic practicality. Thus, rural inhabitants strongly argue that car ownership is a worthy investment, leading to greater quality of life and significant savings in the long term.

Cultural Significance of Mobility in Rural Communities

Cultural perceptions dramatically shape attitudes toward mobility and transportation. In bustling cities, public transport and ridesharing options are readily embraced and often praised. However, rural citizens recount a different story; they frequently express exasperation at sparse taxi services that are often unreliable. A resident’s anecdote about waiting hours for a cab during rain underscores the frustrations of lacking reliable public transport. For these individuals, owning a vehicle is not merely about convenience; it represents a lifeline to independence and spontaneity. As one local put it, 'My car is my ticket to freedom.' This sentiment echoes widely, illustrating that to rural dwellers, cars embody more than transportation—they symbolize a choice to explore, a connection to their surroundings, and the ability to live life on their terms. Ultimately, the car serves not only as a means to an end but also as a crucial indicator of personal freedom and social engagement.

Loading...