Understanding the Mysteries of Bird Flu in Australia

Overview

- Australia stands tall as the last bastion against the H5N1 bird flu virus.

- Geographical isolation and endemic species form a robust shield for the continent.

- Proactive monitoring of migratory birds is essential as the threat consistently evolves.

Geographical Isolation: The Natural Barrier

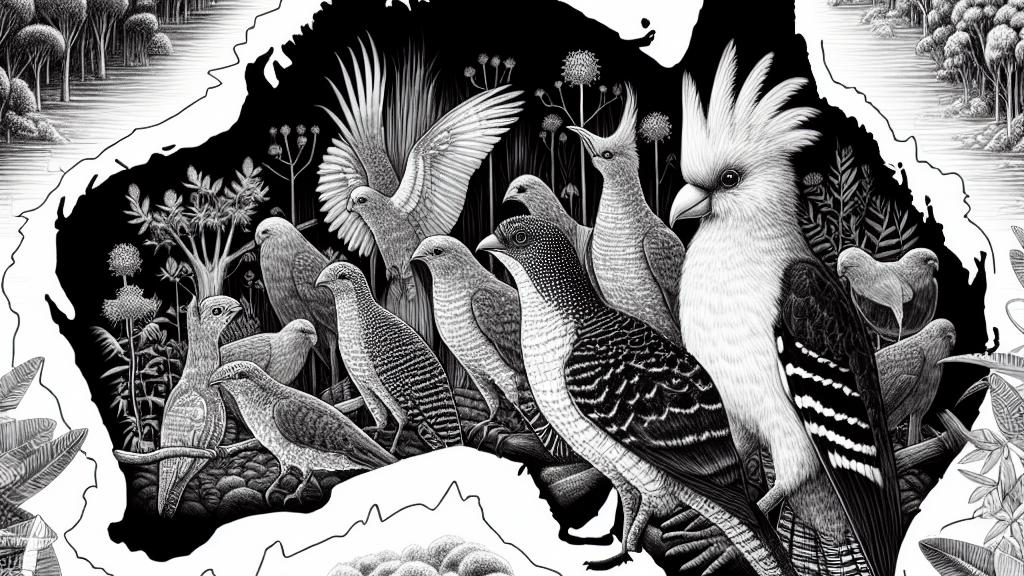

Australia's geographical isolation is akin to a natural fortress, effectively protecting it from the H5N1 bird flu virus. In contrast to many nations that grapple with the dangers of live poultry imports, Australia remains firm in its policies, drastically reducing the risk of viral incursion. Interestingly, most native birds, such as the striking lyrebird and the playful cockatoo, are endemic, and they seldom migrate to regions where the virus prevails. This unique situation can be explained by the Wallace Line, a crucial biogeographical boundary first identified by the naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace in the 19th century. This boundary not only separates distinct species but might also mean that the local avian populations are not as susceptible to adapting to the virus, thus providing a vital layer of protection.

Monitoring Migratory Birds: A Vital Undertaking

As the seasons change, so does the urgency of monitoring migratory birds, whose journeys bring them to Australian shores. Migratory species, notably those making their way from Siberia and Alaska, may unknowingly carry the H5N1 virus, posing a formidable risk. Picture the wedge-tailed and short-tailed shearwaters—spectacular birds that travel great distances—arriving after their long journeys. To mitigate this risk, scientists have launched proactive efforts to swab these migratory birds for the virus upon their arrival. Imagine researchers adeptly capturing shearwaters during their nocturnal resting periods, employing both skill and strategy. They meticulously test each bird for the presence of the virus and check for antibodies that provide insights into potential past infections. Such vigilant monitoring underscores the importance of preemptive measures, showcasing a commitment to environmental health and the protection of native wildlife.

Anticipating Future Threats: The Need for Vigilance

Despite the current safeguarding measures, experts agree on a disconcerting reality: the potential arrival of H5N1 in Australia is not just possible—it's inevitable. This looming threat affects not only birds but also mammals, including seals and other scavengers, bringing catastrophic consequences to ecosystems if the virus spreads. Take the Bar-tailed Godwit, for instance—a remarkable migratory bird that could be at risk due to its lengthy travels. Conservationists emphasize the urgent need for vigilance, especially as spring heralds the arrival of migratory shorebirds. Public awareness campaigns are critical; people should be encouraged to report sick or dead wildlife to authorities for further investigation. Recognizing the signs of avian flu in birds, such as lack of coordination or respiratory issues, could prove vital. In conclusion, combining proactive knowledge with community involvement stands as the best defense against any future incursions of bird flu, ensuring the preservation of Australia's unique wildlife.

Loading...