Research Suggests Water Flooded the Early Universe, Possibly Allowing Life to Form Soon After the Big Bang

Overview

- New research reveals that early supernovae may have produced immense amounts of water.

- Key elements necessary for life could have formed just 100 million years after the Big Bang.

- These findings open thrilling possibilities about the origins of life in the cosmos.

Water's Crucial Role in the Birth of Life

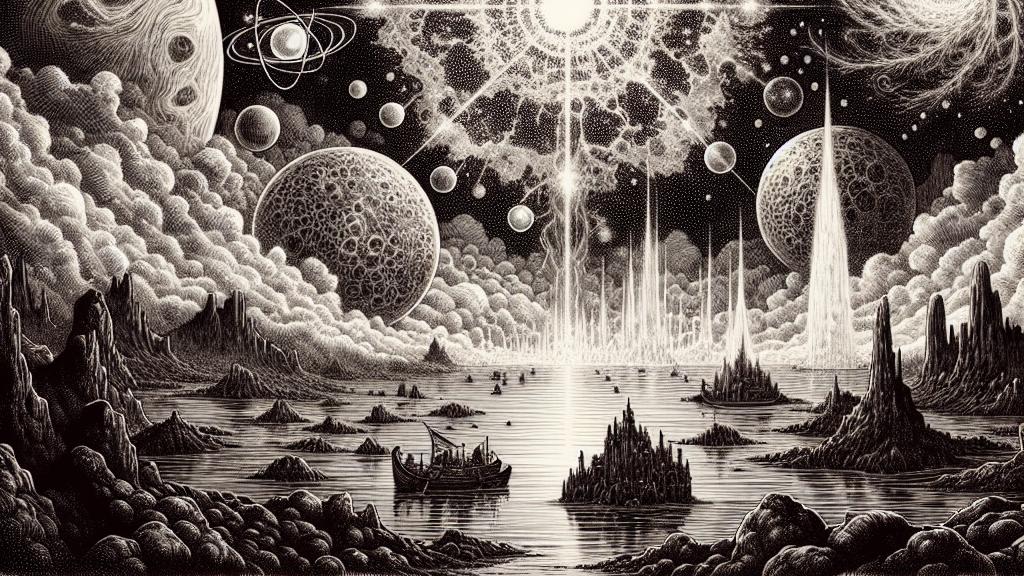

Imagine a universe fresh from the cataclysmic Big Bang—a realm largely composed of hydrogen and helium, teetering on the brink of life. For a long time, scientists believed that it took eons for water, that precious life-giving substance, to emerge. However, recent groundbreaking research has thrown this notion into question! It proposes that early supernovae—massive stellar explosions—didn't just spread cosmic debris; they may have unleashed astonishing quantities of water vapor into the universe. This significant revelation suggests that water could have been present merely 100 million years post-Big Bang, creating a nurturing environment ready for life to sprout. Imagine it like a cosmic garden, booming with potential!

Unraveling Cosmic Mysteries Through Simulations

A dynamic team of researchers from the University of Portsmouth dove into the depths of cosmic exploration, employing innovative simulations to investigate the aftermath of early Population III stars as they exploded. These massive celestial giants, many times the size of our Sun, experienced fiery conclusions, leading to vibrant cosmic fireworks that scattered essential elements across the universe. The results were staggering—these explosive events created dense clouds containing water at densities potentially 30 times what we observe in our own Milky Way galaxy. Just think about it: these dense clouds could serve as an incredible reservoir where the very building blocks for life began swirling together! It's as if the universe was orchestrating a perfect symphony for life's emergence.

The Formation of Life's Foundational Elements

In a dazzling twist, other studies hint that carbon—a fundamental component for all known life, integral to molecules like DNA—might have started forming as early as 350 million years after the Big Bang. Exciting, isn’t it? This potential early union of abundant water and carbon paints a fascinating picture of primordial conditions ripe for life. It’s easy to imagine a primordial soup brimming with possibilities, where the first microbial life forms could have thrived, absorbing these ingredients from their environment. These scenarios shimmer with promise, suggesting that life might have been more likely to emerge than we previously believed.

Challenges and Unexplored Mysteries Awaiting Discovery

Yet, with all this thrilling potential, we find ourselves facing challenges as we venture into the unknown. Take Population III stars, for instance—the celestial architects of early life—these enigmatic beings have yet to be directly observed. Their brief existence leaves scientists grappling with unanswered queries about their role in shaping the evolutionary journey of the cosmos. If, indeed, water poured into the vast expanses of space shortly after the Big Bang, what followed? Did this water set the stage for life's inception, and if so, where did it all go? Such tantalizing mysteries beckon further exploration, urging us to peel back the layers of the cosmic narrative, all while keeping the question of our very existence at the forefront of our quest.

Loading...