AI Uncovers Racial Restrictions in Property Documents

Overview

- Revolutionary AI technology is uncovering hidden racial restrictions embedded in property records.

- California's progressive law mandates the removal of racially charged language from real estate deeds.

- A groundbreaking collaboration between Stanford University and Santa Clara County accelerates this crucial initiative.

Understanding the Legacy of Racial Restrictions

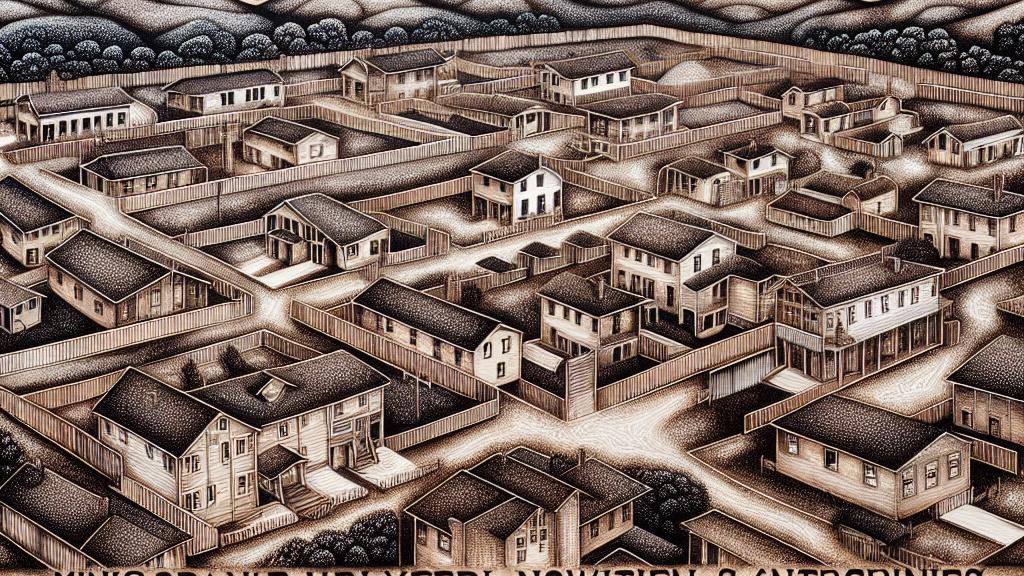

The pervasive issue of racial restrictions in property documents unveils a troubling legacy of systemic discrimination. These restrictive covenants have deep roots, originating in the early 20th century, when they were designed to uphold segregation and prevent non-white individuals from accessing homes in predominantly white neighborhoods. In Santa Clara County, a shocking revelation surfaced: nearly one in four properties contained these discriminatory clauses well into the 1950s, illustrating how deeply ingrained such biases were. For instance, many deeds explicitly barred occupancy by anyone of African, Japanese, or Chinese descent. Despite being declared legally unenforceable in 1948, these prejudiced provisions remained, highlighting a crucial challenge in correcting historical injustices.

Legislative Change Meets AI Innovation

In response to this pressing issue, California took a bold step forward in 2021 by enacting a pioneering law that requires counties to identify and remove racial restrictions from property records. However, tackling the daunting task of auditing over 24 million documents in regions like Santa Clara County demanded a novel approach. Enter artificial intelligence: Santa Clara County partnered with Stanford University's Regulation, Evaluation, and Governance Lab to harness the power of AI. This cutting-edge collaboration led to the development of an advanced language model capable of detecting racially restrictive language with impressive accuracy. As a result, they estimated savings of around 86,500 person-hours, showcasing not only significant efficiency gains but also a smart integration of technology to address historical wrongs.

Revealing Insights into Historical Practices

The use of AI extends beyond simple document editing; it has become a powerful tool for unveiling critical insights into the historical practices of housing discrimination. Studies revealed that approximately one in four properties in Santa Clara County was subject to racially restrictive covenants, a staggering statistic that sheds light on the ubiquity of these injustices. Furthermore, researchers found that a mere ten developers were responsible for one-third of these covenants, exposing a concentration of power that significantly shaped housing patterns in the area. By cross-referencing historical maps with property records, the project paints a vivid portrait of how discriminatory practices manifested spatially, offering a clear understanding of the long-lasting effects of these barriers on communities today. Such research not only emphasizes the importance of rectifying past wrongs but also serves as a critical reminder of our responsibility to create equitable spaces for future generations.

Loading...